If J. K. Rowling had given Jasper Fforde permission to document a decade of derring-do in Diagon Alley, the result would read rather like Rotherweird, an appetising if stodgy smorgasbord of full English fiction set in a town unlike any other.

Like everyone else, Oblong had heard of the Rotherweird Valley and its town of the same name, which by some quirk of history were self-governing—no MP and no bishop, only a mayor. He knew too that Rotherweird had a legendary hostility to admitting the outside world: no guidebook recommended a visit; the County History was silent about the place.

Yet Rotherweird is in need of a teacher, and Oblong—Jonah Oblong, whose career in education to date has been a disgrace—is in need of a job, so he doesn’t ask any of the questions begged by the classified ad inviting interviewees to the aforementioned valley. Instead, he packs a bag, takes a train, a taxi, and then—because “Rotherweird don’t do cars,” as his toothless chauffeur tells him—”an extraordinary vehicle, part bicycle, part charabanc, propelled by pedals, pistons and interconnecting drums,” and driven by a laughably affable madman.

Need I note that nothing in Rotherweird is as it seems? Not the people, not the public transport, and certainly not the place, as Oblong observes as his new home heaves into view:

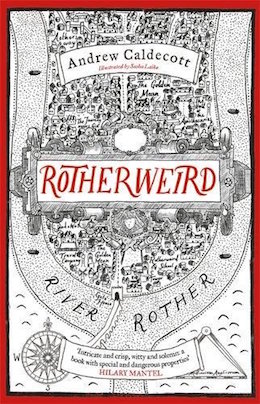

The fog enhanced the feel of a fairground ride, briefly thinning to reveal the view before closing again. In those snapshots, Oblong glimpsed hedgerows and orchards, even a row of vines—and at one spectacular moment, a vision of a walled town, a forest of towers in all shapes and sizes, encircled by a river.

It’s here, in lofty lodgings and under the care of his own “general person,” that Oblong is installed after he’s hired as a history teacher. But the position comes with one stickler of a condition: he has “a contractual obligation to keep to 1800 and thereafter, if addressing the world beyond the valley, and to treat Rotherweird history as off-limits entirely. Here he must live in the moment. Private speculation could only lead him astray.” And if you venture too far off the beaten path in Rotherweird, you might just end up disappeared—the very fate which befell Oblong’s incurably curious predecessor.

Oblong’s hapless arrival in the valley coincides with the entrance—from the sinister side of the stage, let’s say—of another, markedly more meddlesome outsider, who moves into a manor house that’s been strictly off-limits for as long as any of Rotherweird’s many residents can remember. Moolah opens many doors, of course, and Sir Veronal Slickstone has more than enough money to make the mayor look the other way.

More than enough to do that and then some, I dare say, as Slickstone’s wife and son—actors playing elaborate parts proposed to them in the prologue—would attest, if only he hadn’t sworn them to silence at the same time as procuring their compliance. So situated, Sir proceeds to buy the local bar, the better to eavesdrop on all the gossip, before giving a great many guineas to Rotherweird’s greedy antiques dealer in exchange for four strange stones found in a place called Lost Acre: a place—here but not here, if you see my meaning—that may be the key to the unravelling of the entire valley.

The mystery of Rotherweird’s forbidden history is engrossing early on in the novel—the first by QC Andrew Caldecott, though he has, as an “occasional playwright,” dealt in drama in the past—but the longer it goes on, the less appealing said secrets seem, sadly. First the town’s origins are teased, then they’re doled out, piece by piece, in a series of dreams… but Rotherweird’s residents still have to stumble upon their own discoveries, before gathering to discuss, in endless depth and detail, what they’ve learned, not to speak of what these mysteries might mean.

In short, Caldecott suggests, then shows, then tells, and that’s all very well—but then he tells us again, in case we hadn’t quite caught on, then again for good measure, by which point, I’ll be honest, my patience had worn thinner than my grin.

There’s good reason to grin in the early-going, though. Rotherweird isn’t just fascinating in its first act, it’s also funny. Oblong’s oafish entrance sparks off a riotous romp, wittily written, and the other characters we meet in this section of the text, from Vixen Valourhand to Sidney Snorkel, are either equally quirky or morally murky. Alas, they are little more than that, in no small part because the cast expands and expands until the stars of the narrative—never mind the best of the bit players—are hard to pick out from the crowd.

That’s Rotherweird through and through, in truth. It starts off strong, loses its focus after a fantastic first act, surrenders its momentum whilst meandering in the middle, before the curtains come down on a set-piece that isn’t an ending so much as it is scene-setting for the sequel.

That come the conclusion “the company had only scratched the surface of the connections between Rotherweird and Lost Acre” should be exciting, I’m sure. Instead, it’s an exhausting thought. Who knows? Perhaps I’ll have gotten my appetite back by the time Wytnertide is in the wild, but like that big breakfast we began with, as good as this particular book looks, and as delicious as it is initially, it mistakes quantity for quality, leading to a mediocre meal that may have been great if it had only been served on a smaller plate.

Rotherweird is available from Jo Fletcher Books.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He lives with about a bazillion books, his better half and a certain sleekit wee beastie in the central belt of bonnie Scotland.